(aka that really long article)

Newsletter from the anti-apartheid movement

Today UC Berkeley promotes and advertises itself for its “legacy of radical activism,” yet its main role in radical movements is often as the enemy!

This is because angry and oppressed students have not struggled with the liberal university against a discriminatory and unjust society, but against the university itself!

The most powerful movements of all have been those broad movements which extend far beyond the campus to strike at the heart of the american war and consumerist culture. These struggles are difficult and get met with intense repression, yet each is like a firecracker in the dark — sending off thousands of sparks, showing that another world is possible if we want it!!

Golden State Blues

The place now known as berkeley is xučyun territory, the home of the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone people.

The first thing to know about the university of california is that it was a settler institution, created by colonists who came from the east coast with dreams of Manifest Destiny and profit.

Early UC trustee and railroad magnate Frederick Billings supposedly named the Berkeley campus because he was inspired by a poem called “Westward the Course of Empire takes its Way,” authored by Bishop George Berkeley.

From 1849 to 1870, a combination of armed death squads, murders carried out by individual settlers, and the spread of foreign infectious diseases such as smallpox and cholera killed more than 85% of the indigenous population of california – a massive genocide. In 1868, UC was founded and would be granted huge swaths of land stolen from indigenous peoples. This violence and displacement was taken for granted, and even in the interest of many trustees who eagerly looked towards the profits that could be made from the sale of the land and the opening of new pacific markets.

Although it had a “race neutral” admission policy, UC was run by and intended to serve Anglo/white settlers. Still, what few records are available show some Mexican/mestizo and Asian students managed to enroll in the early years, and perhaps others.

The Berkeley Campus

While today it is hard to imagine UC without the other campuses in LA, San Diego, Merced, etc., until the 20th century Berkeley was the University of California. This is where the nickname “Cal” comes from. Students came from all over california to Berkeley for higher education.

Berkeley was a white settler community, with a 96.8% white population in 1926. The city was de-facto segregated, with neighborhoods such as Claremont marked by pillars which explicitly marked them as “sundown” white-only areas. A 1920s census recorded 507 Black people and 1,333 people of Asian descent, who were mostly workers in industrial or service jobs.

One early manifestation of the u.c.’s investment in militarism was its support of Berkeley’s first chief of police, August Vollmer, a.k.a. the “father of modern law enforcement.” Vollmer, a professor of police administration at Cal, developed the military tactics he learned during the u.s. imperialist war in the Philippines into standard practice for domestic police. His goal was to take war strategies and apply them in the internal colonies at home. Professor Vollmer believed crime was part of “racial degeneracy,” and referred to the patrol car (of which Berkeley had the first fleet in 1913) as “the swift angel of death.” He later became L.A.P.D. chief, expanding police power across the nation.

Depression and the Co-ops

In the 30’s, the Great Depression hit. Many students at Berkeley went across the bay to support the labor movement on the picket lines in the 1934 San Francisco general strike. Other students became scabs. Many students were broke and took a page from self-help cooperatives operating in the Bay Area such as the Unemployed Exchange Association (UXA) by forming a student-run and -owned cooperative now known as the Berkeley Student Cooperative (BSC).

UC’s Bombs

In 1945, the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, developed by UC at Los Alamos National Labratory. Hundreds of thousands were killed and many more injured.

In 1946, the US government told the hundreds of resident islanders at Bikini Atoll to abandon their homes, families, and fishing to “temporarily” relocate so bombs could be tested there. The navy moved them to an island one-sixth the size that had very little water or food. What was supposed to be temporary turned into a permanent displacement — UC and military scientists poisoned their island for generations with “near-irreversible environmental contamination.”

UC atomic scientist Edward Teller commented on a man killed by the tests, “It’s unreasonable to make such a big deal over the death of a fisherman.”

Civil Liberties and Civil Rights

The 1950s were a time of the McCarthy anti-communist (and anti-queer) witch hunts. UC faculty began a several year struggle against a mandatory “loyalty oath” to pledge allegiance to amerika and against communism. Although receiving broad student support, the faculty chose not to include students, workers, or other marginalized people in their fight so that their “role as gentlemen” would not be compromised. To the faculty’s rude surprise, the Regents weren’t so gentlemanly in their successful strategy of isolating the more outspoken faculty and setting the demoralized remainder at each others’ throats. This marked the end of a tradition of faculty initiation of university reform.

During the 50s, off-campus speakers were not allowed, political groups couldn’t meet, and the Daily Cal editor met with the administration to plan the paper. The chief administrator of student affairs had been on record for over a decade declaring that moves to racially integrate fraternities were part of a communist plot.

During the national civil rights movements, student organizers with a group called SLATE campaigned for an end to racial discrimination in Greek letter houses, fair wages and rent for students and protection of academic freedom, which at the time meant free speech and an end to political firings of faculty members.

In May, many were angered when a student was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Several hundred noisy demonstrators were kept out of the hearings which were being held in San Francisco. Without warning police opened up with fire hoses washing the students down the steps of city hall. 12 were injured and 64 arrested. 5,000 showed up the next day to protest.

During the summer and fall of that year the administration attacked activism on campus by throwing graduate students out of the ASUC and censoring the Daily Cal. In 1961, Malcolm X was barred from speaking on campus on the grounds that he was a minister; of course, other ministers had been permitted to speak before.

From 1961-63, there was constant conflict between students and the administration over civil liberties issues. The administration was steadily forced to make concessions. The campus was opened up to all outside speakers and compulsory military ROTC for all men was dropped.

In 1963-64 campus political activity in Berkeley focused on anti-Black employers. Students picketed downtown merchants, Lucky Supermarket, Oakland Tribune, a restaurant chain and Jack London Square to protest racial discrimination in hiring. Sit-ins and picketing of the Sheraton Palace Hotel and the Cadillac agency in San Francisco brought industry-wide agreements to hire Black people for jobs.

Because veterans were entitled to higher education through the G.I. bill, many many more Black, Chicanx, Asian and Indigenous students were enrolling at UC schools during these decades. The campus was probably a more dynamic and multicultural place than it is now, though of course the administration and faculty did not reflect this.

The Free Speech Movement

From 1960 to 1964, students had greatly strengthened their political and civil rights, and many more became involved in broader, off-campus struggles. The Free Speech Movement (FSM) in October of 1964 was the most famous demand for student civil liberties at Berkeley.

Traditionally, students had set up political tables on the strip of land at the Telegraph/Bancroft entrance to the university since this was considered to be public property. However, the Oakland Tribune (which students were then picketing) pointed out to the administration that this strip of land actually belonged to the university.

When the university announced that students could no longer set up their tables on “the strip,” students organized and defied the ban through direct action. They deliberately set up tables where they were forbidden and collected thousands of signatures of students who said they were also sitting at the tables.

A police car moved up and the cops took into custody a man sitting at a CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) table. First one, then two, then thousands of people rebelled and trapped the car on Sproul Plaza for 32 hours. The car became a speakers’ platform from which many spoke grievances against and demands of the university.

The governor of california declared a state of emergency by request of u.c. president Clark Kerr, and sent hundreds of cops to the campus.

In a complex struggle with many tactical phases extending over two months, the FSM exposed and isolated the administration and regents so effectively that a notice of disciplinary proceedings against four FSM leaders triggered a sit-in of 800 students and a student strike of up to 20,000.

This forced Kerr to go before a gathering of 18,000 in the Greek Theater with some pseudo-concessions. When FSM leader Mario Savio attempted to speak, the administration ordered UC police to drag him off stage. But they underestimated students’ dedication to the FSM. This repression caused increased anger and activated the campus more. The eventual settlement greatly expanded student political rights on campus.

The ability of Berkeley students to win a sustained struggle gave new strength to students in universities all over the country.

Opposition to the Vietnam War

In the late 1960s, the anti-war movement grew and students focused on the draft and the university’s role in military research. The number of troops in Vietnam increased from an initial 125,000 to 500,000 by early 1968 and tens of thousands died. Protesters responded with a gradual increase in militancy.

About 30,000 people turned out in spring 1965 for a huge outdoor round-the-clock teach-in on a playing field (where Zellerbach Hall is now located).

During the summer of 1965 several hundred people tried to stop troop trains on the Santa Fe railroad tracks in West Berkeley by standing on the tracks. In the fall, 10,00-20,000 people tried three times to march to the Oakland Army terminal from campus. Twice they were turned back short of Oakland by masses of police.

In the spring of 1966, a majority of students voted for immediate US withdrawl from Vietnam in a campuswide referendum initiated by the Vietnam Day Committee. Graduate student TA’s used their discussion sections to talk about the war in one third of all classes. Soon after the vote, the VDC’s offices were bombed and thousands students responded by marching on Telegraph Ave.

A new level of militancy was reached in the fall of 1967 with the Stop the Draft Week in Berkeley. Actions at the Oakland Induction Center and teach-ins on campus were planned. The Alameda country supervisors got injunction to forbid the use of the university for “on campus advocacy of off campus violations of the Universal Military Training and Services Act.” On Monday evening, returning from Oakland, 6,000 demonstrators found that the auditorium which they had reserved was closed and on-campus meetings were banned.

Tuesday morning police broke up a demonstration at the Induction Center with clubs and mace, injuring several dozen including medics and news reporters. On Friday the protesters returned, ready to stop the buses of troops from leaving and ready to defend themselves. They numbered 10,000 and many wore helmets and carried shields. They built barricades, stopped traffic and spray-painted a twenty-block area while dodging police.

Eldridge Cleaver’s Class

During the late 60s, the Black Panther Party became hugely influential in Oakland, organizing meal programs and self-defense against police, prisons, and government repression.

In summer 1968, there were riots on Telegraph Ave against police harassment on Southside and an underlying spirit of rebellion. A spark that caught fire on campus in the fall was the decision of the Regents to limit guest speakers to one appearance per quarter per class, which effectively stripped the credit from Social Analysis 139X – a student-initiated course on racism in amerika, featuring well-known Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver as the principal lecturer.

After weeks of meetings, rallies and negotiations, the students in the class took the initiative. They held a sit-in in Sproul Hall. About 120 were arrested, while hundreds more massed outside.

Two days later another sit-in was held at Moses Hall, organized by radicals who planted barricades against forced entry. About 80 were eventually arrested. (The administration seized on some alleged property damage to divide the students, and the struggle dwindled due to division over tactics, the burden of court and disciplinary proceedings, and end of the quarter.)

The Third World Strike

The next quarter saw the Third World Strike at Berkeley. This greatly overshadowed the Cleaver struggle and any other struggle on campus up until that point.

For the first time, Third World students on campus led a major, campus-wide struggle around self-determination and demands relevant to BIPOC students, faculty, and workers.

Three Third World groups had been involved in separate smaller negotiations and confrontations with the administration for a year. Under the influence of the strike at San Francisco State, these Berkeley students formed the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) and put forward their demands, chief among them a Third World College with adequate funding, open admissions and financial aid for Third World people and Third World control of these programs.

The first stage of the struggle was mainly an attempt to educate the campus. Picket lines were set up, along with a program of dorm speaking, convocations and circulation of literature. Then there were blockades of Sather Gate and the Telegraph Ave entrance. Police were mobilized on campus and students responded by marching through buildings to disrupt classes.

Governor Reagan declared a “state of extreme emergency” and placed control of the campus in the hands of Alameda County Sheriff Madigan. The administration and police began a brutal campaign to crush the strike. Picketers were arrested and beaten in the basement of Sproul Hall. Leaders were arrested. All rallies and public meetings on the campus were banned. But the demonstrations got bigger and bigger. On campus, police fought against students with tear gas and clubs; students responded with rocks and bottles. Hundreds were injured or arrested.

After two months of strike, students were worn down and exhausted by court battles. A divisive debate about tactics had arisen. Under the circumstances, the TWLF decided to suspend the strike. They entered into negotiations with the administration over specifics of an Ethnic Studies program, which, while falling short of their demands, was a partial victory and created today’s Ethnic Studies departments.

The Battle for People’s Park

In 1968, u.c. took all 30 buildings on the block between Haste and Dwight that is now People’s Park. Affordable units and homes from unwilling sellers were seized through eminent domain. The university evicted all tenants and demolished the entire block.

A year later, it was still an empty and unused lot. This led people to liberate the land, by bringing sod and turning it into a garden. People’s Park was created on the muddy, abandoned lot by thousands of students and other volunteers. Swing-sets, art, plants and free meals bloom.

On May 15th, 1969, known as Bloody Thursday, in violation of negotiations with Park creators, u.c. attacked and fenced off the new, green, gathering space.

A rally protesting the fence was quickly organized on Sproul Plaza. In the middle of the rally, police turned off the sound system. 6,000 people spontaneously began to march down Telegraph toward the park. They were met by 250 police with rifles and flack-jackets. Someone opened a fire hydrant – when cops moved into the crowd to shut off the hydrant, some rocks were thrown and the police retaliated by firing tear gas.

An afternoon of chaos and violence followed. Sheriff’s deputies walked through the streets of Berkeley firing into crowds and at individuals with shotguns. At first they used birdshot but when that ran out, they switched to double-0 buckshot. 128 people were admitted to hospitals that day, mostly with gunshot wounds. James Rector, who had been watching from a roof, died of his wounds a few days later.

The day after the shootings, 3,000 National Guard troops were sent to occupy Berkeley. A curfew was imposed and a ban on public assembly was put into force. Meetings on campus were broken up with tear gas. But mass demonstrations continued. Mass arrests occurred. 482 people, including passerby and journalists from the establishment press, were arrested in one swoop. Prisoners from that arrest reported extensive beatings at Santa Rita jail.

At a rally on Sproul plaza, troops surrounded the gathering, admitting people but preventing them from leaving. Then the troops put on gas masks and a helicopter flew over spraying CS tear gas, a gas outlawed for wartime use by the Geneva Convention. They mistakenly teargassed Cowell hospital as well as several local public schools.

Mass unrest continued in Berkeley for 15 days after the park was fenced and finally 30,000 people marched peacefully to the park. The fence, however, stayed up.

During the summer of 1969 on Bastille day protesters marched from Ho Chi Minh (Willard) park to People’s Park. Organizers had baked wire clippers into loaves of bread and lo and behold – the fence was down, and the park was temporarily liberated.

1970s: Anti-Imperialism

On the April 15 Moratorium Day against the Vietnam war, Berkeley students attacked the Navy ROTC building. The university declared a state of emergency. Campus was still under a state of emergency when the media announced the invasion of Cambodia. Activists at Yale called for a national student strike over the Cambodian invasion and the strike spread even more when news came about national guard murders at Kent State, Jackson State and Augusta.

Berkeley students paralyzed the school with massive rioting the first week of May. Students went to their classes and demanded that the class discuss the Cambodian invasion and then disband. 15,000 attended a convocation at the Greek Theater and the regents, fearing more intensified riots, closed the university for a four-day weekend.

The Academic senate voted to abolish ROTC but the regents simply ignored the vote. A faculty proposal sought to “reconstitute” the university so students could take all classes pass/not pass and could get credit for anti-war work. Thousands of students participated.

In the fall of 1970 a War Crimes Committee (WCC) was formed by radicals to attack the university’s role in the amerikan war effort. Two hearings were held and attended by thousands and after the second, an angry crowd tried to march to the house of right-wing atomic scientist Edward Teller.

In February, when American troops began an invasion of Laos, WCC called a rally on Sproul Plaza and thousands showed up, the biggest gathering of the year. They marched to the Atomic Energy Commission building on Bancroft to protest the deployment of nuclear weapons in Thailand. After police provocation, skirmishes broke out and an AEC car was burned.

During the spring of ‘72, a coalitions of groups formed into the Campus Anti-Imperialist Coalition (CAIC) to oppose the increase of the bombing of North Vietnam. CAIC and other groups organized an April 22nd march of 30-40,000 people. They demanded enactment of the Seven Points peace plan, which was proposed by the North Vietnamese. A national student strike was called.

At Berkeley, construction workers had gone out on strike to protest administration efforts to break their union. Other campus unions joined the strike. At the same time, Chicano students and other Third World groups held a sit-in at the law school (then known as Boalt, named after an anti-Chinese racist) to demand more admission of Chicano and other BIPOC students.

A massive, campus wide strike, including both workers and students, was beginning to emerge. Students held huge meetings, rallies and spirited marches, joined the workers on the picket lines and covered the campus with garbage, to be picked up later by scabs guarded by the police. Active students were banned from campus. The strike lasted for 83 days.

In Early May, candlelight march was hastily called in Ho Chi-Minh Park to respond to Nixon’s latest acts of war. Starting with only 200-300 people, it grew to thousands as they marched through Berkeley. Campus administrators had re-fenced People’s Park, and that night, people tore down the fence with their bare hands. A police car was overturned and burned. Skirmishing with police lasted into the morning hours.

In the fall of 1972, the Black Student Union (BSU) mobilized against the absorption of the Black Studies Department into the regular academic College of Letters and Science. The department had been won as part of the Ethnic Studies Division during the Third World Strike. A BSU led boycott only lasted for a quarter but was defeated. The chancellor then closed the Research Institute on Human Relations, which had also been created by the Third World Strike.

During the school year, radical students from the Education Liberation Front formed alternative discussion sections for large social science classes. Members of the alternative sections would study together and challenge the professor’s “apolitical education” and the whole content of the course during lecture!

In the early 1980s, the struggle against imperialism would continue. Thousands organized, marched, and held sit-ins against u.s. intervention in El Salvador.

Disability Liberation

In the 60s, students at Cal with disabilities had started a movement to get basic rights – adequate accessible housing, services, educational facilities, books, etc. Many innovations such as the now ubiquitous “curb cuts,” where sidewalks dip down to allow wheelchairs to cross the street, started in Berkeley. People with disabilities organized, started communal places to live together when they couldn’t find accessible housing or a safe place from discrimination and ridicule.

A national militant movement of “an army of cripples” demanded and has won major changes over the decades, including the passage of the ADA which guaranteed basic access standards. Yet accessibility still remains elusive, and Cal has often attempted to shutter accessible housing near campus – including trying to do a hostile takeover in 2012 of the Rochdale/Fenwick co-op, which had some of the first cheap and accessible rooms near campus.

Anti-Nuclear Action

In early 1982, students and other local activists began mass blockades of Livermore Lab, another major nuclear weapons research and design facility operated by UC for the u.s. government.

LLNL has released a million curies of airborne radiation, roughly equal to the amount of radiation released by the Hiroshima bomb. Lab documents disclose that Livermore wines contain four times the tritium found in other California wines, and a California Department of Health Services investigation found that children in Livermore are six times more likely to develop malignant melanoma than other children in Alameda County.

In June, over 1,000 people were arrested at protest against the labs. They were held in circus tents for 10 days (until an agreement was reached) because there were too many to jail.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki Week 1985, about 80 were arrested at the Livermore Labs. This action included powerful disability solidarity. Three women who use wheelchairs were arrested. Alameda County Sheriffs didn’t want to deal with their needs, planning to cite them out. They wanted to remain in resistance with the rest so people refused to enter buses at all until confident these women would be kept with the larger group. All the others promised unrelenting refusal to cooperate if the cops continued to try to separate these women.

Protesters were at Santa Rita for 5 days, refusing to cooperate with any number of orders, pointing out that they were waiting to go before a judge, to have their day in court. When they were ordered to get ready to go to court, it came to light that, there was no ramp into the on-site courthouse. Guards said they would carry the women. Total refusal to cooperate ensued. Protesters made clear: No ramp, no cooperation. A ramp was built and protesters had their day in court, together.

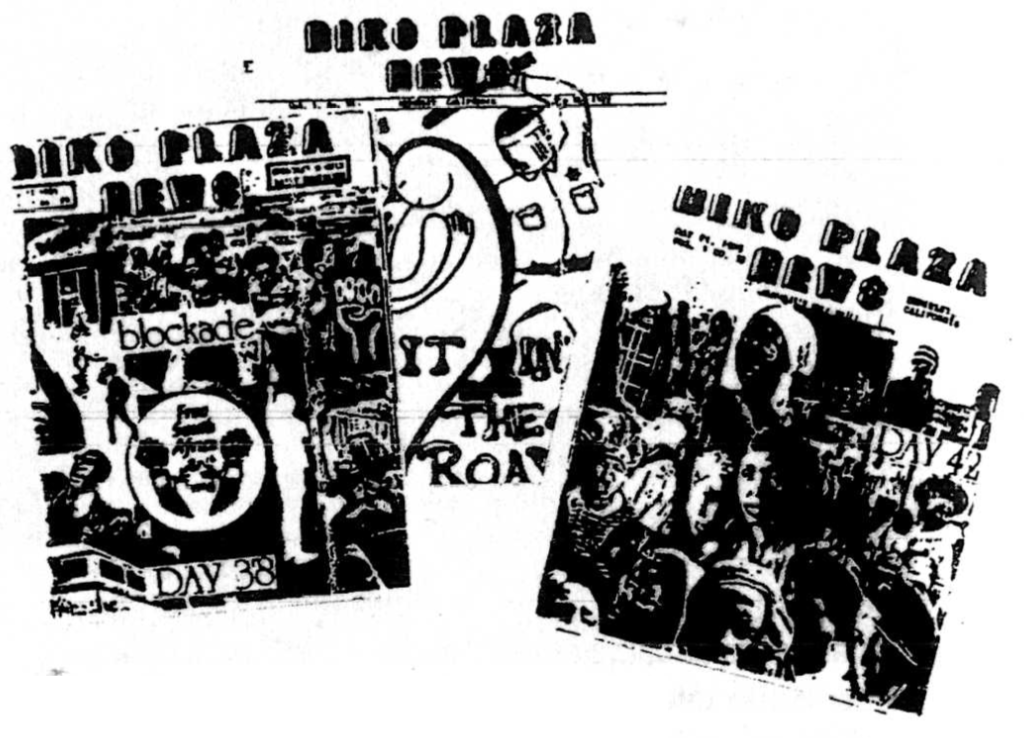

Anti-Apartheid Movement

In early 1977, as a response to the increased struggle in South Africa, new formations began to demand divestment of university holdings in companies doing business in South Africa.

Mass arrests at Santa Cruz and Stanford sparked demonstrations up and down the state including a sit-in at Berkeley.

In 1984, the United People of Color (UPC) and the Campaign Against Apartheid (CAA) joined forces in the UC Divestment Coalition. They demanded that the university divest the $1.8 billion it had invested in South Africa.

Students plastered Sproul Hall with banners and signs and renamed it Biko Hall, after the murdered South African Black Consciousness Movement leader, Stephen Biko. On April 15, 350 slept out and UCPD began making arrests at 4:30 am.

Police arrested over 160 protesters and it took so long that the bust was still going on when students arrived on campus for their 8 am classes. Students were angered at the violence of the police. That day 5,000 gathered to hear FSM leader Mario Savio speak in support of the “Biko 160+.” Organizers of the rally called for a student strike the following day and that night over 600 people slept on the steps.

At the end of March, CAA and UPC achieved a tenuous alliance to set up a shantytown together in front of California Hall. After 4,000 rallied in Sproul Plaza, students marched to California Hall and built a couple dozen shanties. After midnight, police brutally arrested 60 protesters who had surrounded the shanties.

Two days later, after the university had issued orders banning leading organizers from campus and sought an injunction banning all protests on campus, several thousand rallied and marched to the edge of campus where banned protesters joined the crowd and marched onto campus. More shanties were constructed.

Over 1000 people remained at the shantytown shortly after midnight when over 250 cops from 16 police departments attacked and swept the arestees off campus before classes started in the morning. Efforts to blockade the buses were met with police clubbing of hundreds.

In June 1985, the regents seemed to turn a new leaf and voted to divest $3.1 billion of investments in companies with South Africa ties. Unfortunately, it was a sham – their investments continued to increase – but this wasn’t discovered until the movement had dissipated.

During this time and after, Third World students organized to create an ethnic studies requirement, demand more BIPOC faculty and tenure for them, stop Ethnic Studies cuts, and get affirmative action in California. 90% of law students struck for similar demands in their school; some students who occupied that administration office were arrested.

As 1983 began, four Chicano students were attacked and beaten by members of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity. Hundreds of students marched in protest demanding the withdrawl of university recognition of the frat. Two days later, with no action yet taken, students occupied California Hall. The university later announced it would withdraw recognition of Beta Theta Pi for two years.

Women Get Organized

Women at Berkeley began to organize during the height of the sit-in and throughout the anti-apartheid movement because they felt they didn’t have a significant voice in decision making, although their numbers equaled those of the men involved. They organized Women Against Oppression to create a forum for women to discuss the sexism occurring within the student movement and as a base for organizing women’s actions within the anti-apartheid movement.

During the Spring of 1988 the African Student Association organized a sit-in at the UC housing office to protest the racial harassment of a black woman in one of the dorms and the general climate of racism in the housing system and on campus. 19 students were cited by the police.

One “women’s lib” group formed in early 1986 from women involved in anti-imperialism and anti-apartheid struggles. In the fall of 1986, they held rallies in support of a young woman who had been gang-raped by four football players. The university protected the football players, while the woman dropped out of her first semester.

Later in the decade, abortion was under siege from Reagan & Co. A campus anti-abortion group was blockading abortion clinics and harassing pregnant women, so a group called RORR formed to protest them. In spring of 1989 they also began a 50 day, 24-hour vigil on Sproul plaza in favor of a women’s right to an abortion.

The spring saw publication of the first issue of Broad Topics, Writings by Women, a journal of women’s poetry and prose that grew out of the Feminist Student Union (FSU). Multi/Multi, the Multi-Cultural/Multi-Racial Women’s Coalition, also provided a new forum for women’s discussion and organization.

Barrington Hall

Also during the fall, with the war on drugs in full swing, students held a smoke-in on Sproul Plaza that attracted 2,000, the largest event of the semester. Barrington Hall, a student co-op that helped organize the smoke-in and that had long been a center of organizing efforts (the Disorientation guide itself was often associated with Barrington) was threatened with closure from a vote within the co-op system. There had been several other votes over the years to try to close Barrington and in November, the referendum passed.

After the vote, residents took legal action to remain in their home and started to squat the building. There had been irregularities in the vote, including involvement on the part of staff who were supposed to be neutral parties. Finally in March, a poetry reading was declared illegal by police who cleared the building by force. A crowd developed which built fires and resisted the police. Finally police attacked, badly beating and arrested many residents and bystanders and trashing the house. Assaults and arrests were primarily targeted at women and the people of color present, who shared their experiences in a 1990 issue of Slingshot. The building is now leased to a private landlord.

Also during the spring of 1990, student protests demanding a more racially and sexually diverse faculty continued. Students occupied the chancellor’s office. After a long educational effort, the United Front, a coalition of groups, called a two day strike for April 19 and 20. Pickets were set up around campus and many classes moved off campus or were sparsely attended. Earlier in the school year, the first issue of “Smell This!” was published, reflecting the increasing organization of women of color.

Organizing around the defense of People’s Park expanded to include opposition to police harassment on Southside. Unhoused people were targeted for removal. Copwatch, a group which monitored police harassment and helped people fight police abuse, was founded.

The (First) Persian Gulf War

As the winds of war gathered strength, several groups turned their attention to preventing it. Students for Peace in the Persian Gulf organized teach-ins and educational events. The Anti-Columbus Coalition, along with students at SF state, organized a militant occupation of the military recruiting center in SF. 13 people were arrested on felony charges.

The day before the war started in early 1991, Roots Against War helped organize a huge march in San Francisco in which the Bay Bridge was taken over. The next day another huge march gradually turned into a rampage and the military recruiting station was trashed, along with some porn stores. A police car was set on fire.

Battle for People’s Park, Again

In the spring of 1991, the university released plans to redevelop People’s Park. They proposed removing the Free Speech Stage and installing several large volleyball courts throughout the park. Bulldozers were ushered in, accompanied by riot police, to install the sand volleyball courts.

A new wave of protest began, with the rallying slogan “Defend the Park,” which was shared in coordinated solidarity with organizers resisting gentrification and the displacement of poor and unhoused people at Tompkins Square Park in the Lower East Side of New York City.

Emergency committees were established, such as the People’s Park Defense Union. Nightly vigils and open meetings were held each night in the summer of 1991. An event hotline was also established to share information about rallies, direct action, and community events to defend the park. As a UC construction team arrived in July 1991, hundreds of protesters gathered to prevent the bulldozer from breaking ground. Several arrests were made.

Protests grew each day, and police escalated to shooting wood pellets and rubber bullets at demonstrators. More than 95 people were arrested in the first four days, and 3 people injured, including a photographer for the San Francisco Examiner. The Examiner later reported the total cost to UC of installing one sand volleyball court to be $1 million.

UC reportedly paid individuals $15 an hour to play volleyball in order to make the courts appear to be in use, with round-the-clock police supervision. When a group slapped away a volleyball during play and dunked it into a porto-potty toilet, police tried to press charges against those responsible.

On December 15, 1991, the Daily Californian reported that a (heroic) “unidentified vandal used a chainsaw to cut down the central wooden post of the volleyball court.” The sand boxes remained until 1997, however, when UC finally removed them from the park.

Free the UC, Occupy Cal

In the 2000s, the regents repeatedly raised tuition while becoming more corporate, outsourcing labor, and honing anti-union, anti-worker tactics. UC Berkeley has become whiter and wealthier since the 90s, and is a major force of gentrification and displacement across the state. Berkeley has become re-segregated in recent decades to become dominantly white; UCLA now runs luxury hotels; the regents make deals with Wall Street and guarantee their profits by raising tuition.

March 19, 2008 was “Free the UC Day,” where a direct action was held in front of the regents’ meeting to have an “Alternative Regents Meeting” with free food and music. People called for free education, democratically elected regents, no more warmongering or military contracts, better wages, and affirmative action.

In September 2009, thousands gathered in Berkeley to protest a proposed tuition increase of 32%. The regents waited a little while, then passed it anyway.

In fall 2011, as Occupy Wall Street gripped the nation and world, a group of students and faculty held “teach-outs around campus” about similar issues, and had a rally and protest around town. Police forcibly removed the remaining participants from Sproul Plaza where they had set up tents. The campus was galvanized as a result and a General Strike was called. Students and professors skipped class. Word spread across the UC, with a particularly strong presence at UC Davis – where police were famously photographed casually pepper spraying students sitting on the ground.

COLA4ALL

In February 2020, grad students at UC Santa Cruz went on a “wildcat strike” – meaning without the blessing of their union, since their contract contained a no-strike clause. The strike spread rapidly to every campus, as many others being exploited by the UC began to build a collective struggle.

Students at UCSC liberated the dining halls to offer free food, classes were canceled due to a strong picket line, and eventually strikers withheld grades and stopped labor for the UC. At its most radical, “COLA” (Cost of Living Adjustment) was not just about more money but a collective demand for UC’s looted wealth to be shared, decolonization of academia, and abolition of cops. The Crossroads dining hall at UC Berkeley was momentarily liberated, before management threw away all the food to prevent people from eating for free. Nonetheless, people chipped in money for pizza and co-opers brought big pots of pasta and salad from their houses.

As things reached a fever pitch with huge rallies stopping labor at many UC campuses, the pandemic hit. The movement diffused as people scattered and avoided crowds. UC wasn’t able to kick out the wildcat strikers and grade strike hold-outs as they had hoped, and were forced to re-instate them. Some token concessions were made. But a spark was lit. While campuses were dormant, flames burned wild in the summer uprisings of 2020 against police murder.

One warm summer afternoon, a small block party was held before a riot in Oakland. A group marched from UCOP headquarters to former UC president and warmonger Janet Napolitano’s luxury condo, carrying the banner “Fuck the UC!” There were free burritos and zines.

These embers are still hot. What’s next is up to us. Defend People’s Park, middle fingers to the UC, and Decolonize Everything!